Rethinking Exposure Therapy for Panic Disorder With Agoraphobia

New Insights Into Why Exposure Therapy Works

"The present results revealed that patients consistently overestimate their fear during exposure therapy. Possibly, predictions and overestimation of fear should be addressed more directly in treatment"

What if the real breakthrough in exposure therapy isn’t about fear itself, but about what clients expect to fear?

Let’s take a step back.

For individuals with panic disorder and agoraphobia, the mind often races ahead, imagining everything that could go wrong before the situation even begins. Yet it’s this —— gap —— between the feared and the actual experience that may drive therapeutic change.

A new study sheds light on how these fear predictions shape treatment outcomes, offering fresh direction for clinicians navigating the complexities of anxiety.

Diagnosing Panic Disorder and Agoraphobia

Panic Disorder and Agoraphobia are distinct mental health disorders that often overlap.

Panic disorder affects 3–5% of the population and is characterized by:

Unexpected panic attacks: Sudden episodes of intense fear that arise without a clear trigger.

Accompanying physical symptoms, such as rapid heart rate, shortness of breath, chest discomfort, dizziness, and a sense of losing control or impending doom

To meet diagnostic criteria, individuals must also experience:

Persistent worry about having additional attacks

Unhelpful changes in behavior, such as avoiding situations that might trigger an episode

Agoraphobia is marked by intense fear or avoidance of situations where escape might be difficult or help unavailable during panic-like symptoms. For example, a person with agoraphobia may fear parking lots, movie theatres, retail stores, crowded places like concerts, public transportation, etc.

While often misunderstood, it's more common than many realize, affecting about 2.6% of people over their lifetime. Each year, roughly 1.7% of the population experiences agoraphobia, with the highest rates among teens (2.0%) and the lowest among adults over 65 (0.4%).

When both conditions are present, clinicians should assign both diagnoses.

Many clients first experience panic attacks, and over time, avoidance can build into agoraphobia. According to the DSM, between 30% and over 50% of people with agoraphobia first experienced panic attacks or panic disorder.

Screening tools such as this one can be used for Panic Disorder. The Severity Measure for Agoraphobia—Adult can be used to gauge the severity of symptoms due to Agoraphobia.

Fortunately, there are effective treatments, with Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) remaining a gold-standard treatment for both conditions. In particular, exposure-based techniques, where a person gradually faces feared situations, help clients rewire their fear responses and reduce symptoms of fear and anxiety.

An interesting 2018 study identified the most effective CBT treatment package for panic disorder. This combination included:

Face-to-face delivery

Interoceptive exposure: Repeated, intentional exposure to feared physical sensations such as a racing heart and shortness of breath to reduce sensitivity and fear

Cognitive restructuring: Identifying and challenging false, harmful, or unhelpful beliefs

Psychoeducation and psychological support: Elements that support engagement and understanding

This CBT approach was 7 times more effective than the least effective combination.

Why Does Exposure Therapy Work?

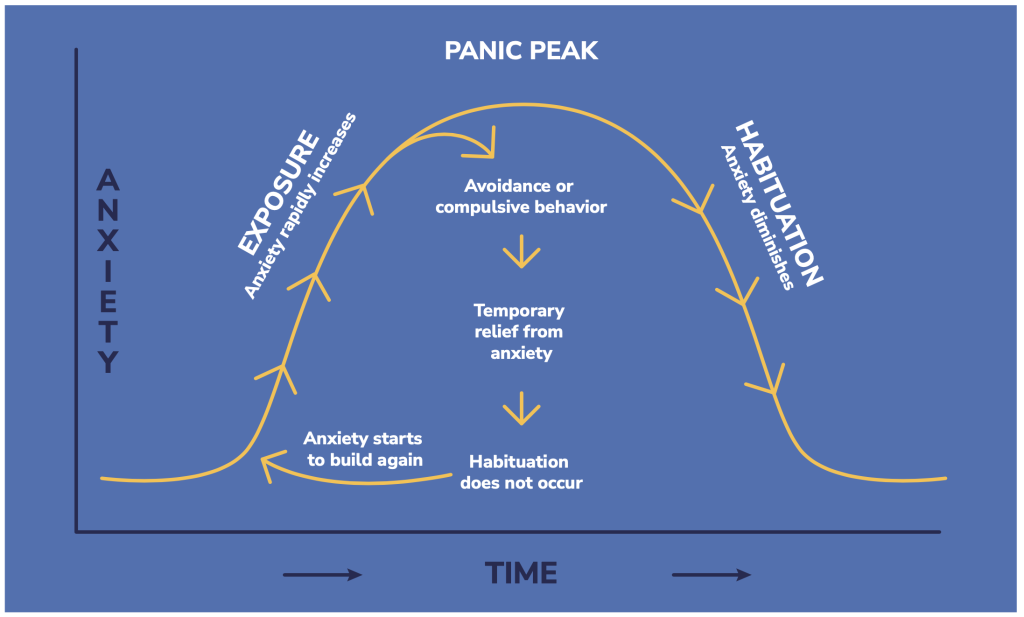

Exposure therapy works by helping people face the things they fear, over and over, until the anxiety starts to fade. This idea, called habituation, has long been the traditional explanation for why exposure works.

Newer research challenges the old idea that people get better just by “getting used to” fear through repeated exposure. Instead, it shows that people may benefit most when their fearful expectations are proven wrong, a process known as expectancy violation.

For example, if someone expects a panic attack to lead to a heart attack, and that doesn’t happen, this mismatch helps weaken the original fear.

One specific version of this idea is called the match–mismatch model. It focuses on how people with anxiety often overestimate how scared they’ll feel in certain situations. When the actual fear they experience turns out to be lower than expected, that “mismatch” can be helpful, but only up to a point.

Interestingly, research shows that the accuracy of fear predictions doesn’t seem to improve much over time and isn’t closely linked to therapy success. What does matter more is that over time, people expect less fear in the first place. In other words, reducing how scary a situation seems ahead of time may be more important than how well people predict their fear levels.

New Research on How Exposure Therapy Works

A 2025 study by Hilleke and colleagues expands on this insight.

Researchers in Germany enrolled 369 adults diagnosed with panic disorder and agoraphobia. All participants received 12 sessions of structured, exposure-based CBT, either with therapist support or as a self-guided program following initial preparation.

The research focused on how clients predict their fear before exposures, how those predictions line up with what they actually experience, and how safety behaviors like avoiding eye contact or carrying medication affect their progress.

They found that:

People Tend to Overestimate Their Fear: At the start of treatment, most clients expected their fear during exposure to be much worse than it actually was. This kind of overprediction is common and fuels avoidance.

Practice Makes Predictions More Accurate: As therapy progressed, clients became better at estimating how much fear they would actually feel, suggesting that experience helped recalibrate their expectations.

More Accurate Predictions, Better Outcomes: Those whose fear predictions improved the most also had the biggest reductions in panic symptoms and avoidance, both right after treatment and at follow-up.

In short, the study shows that getting fear predictions exactly right doesn’t matter as much. Instead, what makes a difference is that both the fear people expect and the fear they actually feel go down over time. The more those fears drop, the better they do in treatment.

Clinical Takeaways

Include objective measurements that can help guide treatment:

The Mobility Inventory is used to assess places and situations that are being avoided

The Panic and Agoraphobia Scale (PAS) measures the severity of illness in patients with panic disorder, with or without agoraphobia

The Agoraphobic Cognitions Questionnaire to measure catastrophic thoughts about anxiety

The Body Sensations Questionnaire (BSQ-18) to measure how strongly someone reacts to physical sensations linked to anxiety or panic.

Make Fear Predictions Part of the Process

Before each exposure, ask your client: “How anxious do you think you’ll feel?”

After the exposure, follow up with: “How anxious did you actually feel?”

Use a simple 0–10 scale. Then compare the two answers together.

Through this, help clients to understand that they will often overestimate how bad the fear will be and that even though their predictions may not become more accurate over time, their overall fear will usually drop. Talking through the gap between expected and actual fear helps clients see that their fears are often exaggerated. This small step helps you both track progress, challenge overprediction, and reinforce what exposure therapy is all about: learning that feared situations are more manageable than they seem.

Target Safety Behaviors: Reducing safety behaviors is important to making exposure therapy more effective. Therapists should work with clients to identify and gradually let go of these habits so the brain can fully learn that the feared outcome doesn’t happen. Common safety behaviors include sitting near exits, avoiding certain places, using distractions like phones, or always having someone else present.

Psychoeducation on Expectancy Violation: Explaining the rationale behind exposure therapy and the importance of expectancy violation can improve a client’s engagement and motivation.

Monitor Change Over Time: Regularly reviewing changes in fear prediction accuracy and safety behavior use can inform treatment adjustments and highlight areas for further intervention.

The Bottom Line

This study shows that exposure therapy works best when people learn their fears are unlikely to come true. While getting used to fear (habituation) still matters, it’s even more helpful when people realize they’ve been overestimating how scary things will be. To make therapy more effective, clinicians should help clients improve their fear predictions and reduce safety behaviors like avoidance or distraction. This can lead to stronger, longer-lasting improvements in anxiety.

“Violating excessive fear expectancies is not a necessary condition for symptom reduction during exposure therapy. However, the reduction in expected fear was a significant predictor of treatment success across all outcome measures in the follow-up assessment.”

Attribution: This summary is based on the article “How Do Patients’ Fear Prediction and Fear Experience Impact Exposure-Based Therapy for Panic Disorder With Agoraphobia? A Comprehensive Analysis of Fear Prediction” by Marina Hilleke and colleagues, published in Depression and Anxiety (2025). All rights to the original research remain with the authors and publisher. This summary is intended for educational purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the original authors1.