Start Here: Sleep Disorders and Mental Health

What Clinicians Should Know About Sleep and Mental Health

Sleep is often treated as an afterthought. But mounting evidence suggests it should be treated as a vital sign, especially in mental health care.

Take schizophrenia: a 2025 Schizophrenia Bulletin review found that disrupted sleep significantly worsens cognitive mental abilities such as memory, learning, and attention, compounding the challenges already faced by patients. Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), which is common but underdiagnosed in this population, further damages these sleep patterns and accelerates age-related decline.

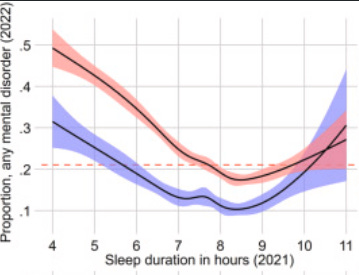

The risks extend well beyond clinical populations. A large 2024 Norwegian study of over 21,000 college students showed that sleep duration alone, whether too little or too much, was a powerful predictor of future anxiety, depression, PTSD, and other psychiatric symptoms. The optimal range? About 8 to 9 hours per night.

The reality is that mental and physical health are deeply connected, and few relationships are as tight as that between sleep and mental health. Poor sleep isn’t just a symptom: it can also be a signal, a risk factor, and a contributing cause of psychological distress.

Sleep is not merely a side effect of distress. It’s often an early clue, a contributing factor, and a driver of worsening outcomes. It’s no surprise that the DSM-5 includes sleep-wake disorders, as they commonly co-occur with mood, anxiety, neurodegenerative, and pain disorders.

Poor sleep impairs the very functions mental health professionals aim to protect: memory, concentration, mood regulation. For example, sleep disruptions like those seen in REM sleep behavior disorder, where a person physically and vocally acts out their dreams, can precede conditions like Parkinson’s. And persistent insomnia can forecast the onset of depression or anxiety long before other symptoms emerge.

Given these facts, recognizing the role of sleep is essential for delivering comprehensive mental health care.

What are the key sleep disorders listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual?

A hallmark of sleep-wake disorders is their impact on daytime functioning: fatigue, mood swings, poor concentration, and memory problems are common.

Insomnia Disorder: Difficulty falling or staying asleep at least three nights per week for three months or more, causing daytime impairment. It affects about 10% of adults and is especially common in women over 45. Insomnia increases the risk of depression, anxiety, and suicidal behavior.

Hypersomnolence Disorder: Excessive daytime sleepiness despite adequate nighttime sleep. It typically begins in late adolescence and can be mistaken for depression or fatigue. It disrupts work and social life and is linked to substance use and mood disorders.

Narcolepsy: Sudden, uncontrollable sleep episodes, often with cataplexy (sudden and brief loss of muscle control), vivid hallucinations, and sleep paralysis. It usually begins in youth and persists throughout a person’s life.

Breathing-Related Sleep Disorders: Conditions like obstructive sleep apnea and central sleep apnea involve pauses in breathing during sleep. They are linked to obesity, cardiovascular issues, and cognitive decline.

Circadian Rhythm Sleep-Wake Disorders: When your body’s sleep rhythm is out of sync with your daily schedule. This is common in shift workers or people who stay up very late. These disorders can lead to chronic insomnia or excessive sleepiness.

Parasomnias: Abnormal behaviors during sleep, including sleepwalking, sleep terrors, and nightmares. REM sleep behavior disorder is notable for its link to future neurodegenerative diseases.

Restless Legs Syndrome (RLS): An uncontrollable urge to move the legs, especially at night, leading to delayed sleep onset and frequent awakenings.

Substance/Medication-Induced Sleep Disorder: Sleep problems caused by substances like alcohol, caffeine, or medications. Effects vary depending on timing, dosage, and withdrawal.

Sleep disorders also often co-occur with psychiatric conditions:

ADHD is associated with insomnia, restless legs syndrome, and sleep-disorder breathing such as sleep apnea

Depression and bipolar disorder frequently involve insomnia or hypersomnia

Anxiety Disorders are associated with sleep-onset difficulties, nocturnal panic, and restless sleep are typical

PTSD has nightmares and sleep disturbances as core symptoms

Neurocognitive Disorders such as Alzheimer’s and related conditions often include disruption of sleep and problems with the body’s circadian rhythm, which regulated the sleep-wake cycle

Clinical Takeaways

Consider referring to a physician and/or specialist

Given the entwined relationship between physical and mental health, professionals should collaborate with sleep specialists, primary care providers, and psychiatrists. Coordinated care can uncover and address medical conditions, like sleep apnea or hormonal imbalances, that might be fueling psychological distress.

Make Sleep a Standard Part of Mental Health Assessment

Sleep is a vital sign for mental health. Ask about sleep duration and quality with every client. Young adults are particularly vulnerable, with short sleep duration linked to higher risk for anxiety, depression, ADHD, and more. Consider using or integrating information from tools such as:

Provide psychoeducation

Help clients understand why sleep matters. Resources like the CDC’s sleep health guidance can support conversations about sleep hygiene, routines, and the consequences of chronic sleep loss.

The Center for Clinical Interventions also has great resources for sleep.

4. Consider training in Interventions that can provide sleep-focused treatment, especially CBT for Insomnia (CBT-I), as these can help people to obtain better sleep, improving their mental health. We previously covered a treatment for insomnia here, which was grounded in CBT-I. Free training on CBT-I here (paid to obtain the CE credits)

____

In conclusion, sleep is one of the underlying threads weaving together physical and mental health. It influences everything from emotional regulation and cognitive functioning to immune response and chronic disease risk. Given this, sleep is a clinical signal, a modifiable risk factor, and a potential pathway to healing. By integrating sleep into routine assessment, psychoeducation, and treatment planning, clinicians can uncover hidden drivers of distress and improve outcomes across diagnoses.

Attribution: This summary was created by the team at Psychvox and is based on insights from the articles “Sleep duration and mental health in young adults” by Cecilie L. Vestergaard and colleagues and “Age-Related Changes in Sleep and Its Implications for Cognitive Decline in Aging Persons With Schizophrenia: A Critical Review” by Bengi Baran and Ellen E Lee. Furthermore, the article uses information from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fifth Edition, Text Revision. All rights to the original research remain with the authors and the publisher. This summary is intended for educational purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the original authors. The articles are licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0).

Photo by Dakota Corbin on Unsplash