Supporting Complex Cases: The Therapist’s Role in Co-Occurring Eating Disorders, Diabetes, and Obesity

Strategies for Navigating the Overlap of Physical and Psychological Care

[Above is an AI-generated read-through of the text summary below, so that you can listen to it on the go]

Starting this week, our Thursday articles will be available exclusively to paid subscribers. If you're already supporting us—thank you.

Why the change? Our mission has always been clear: to bring the most important mental health research directly to professionals in a way that’s accessible, relevant, and actionable. But making that happen at scale—reading through thousands of pages, curating what matters, translating it into practice—requires a team. And building that team takes resources. We’re also looking into integrating continuing education credits, so the time you spend reading this work can also count toward your professional growth.

If you’ve found value in what we’re doing, we’d love to have you as a subscriber. You'll get exclusive Thursday editions, full access to our growing archive, special features—and most importantly, you’ll be helping to make evidence-based care more available to clinicians.

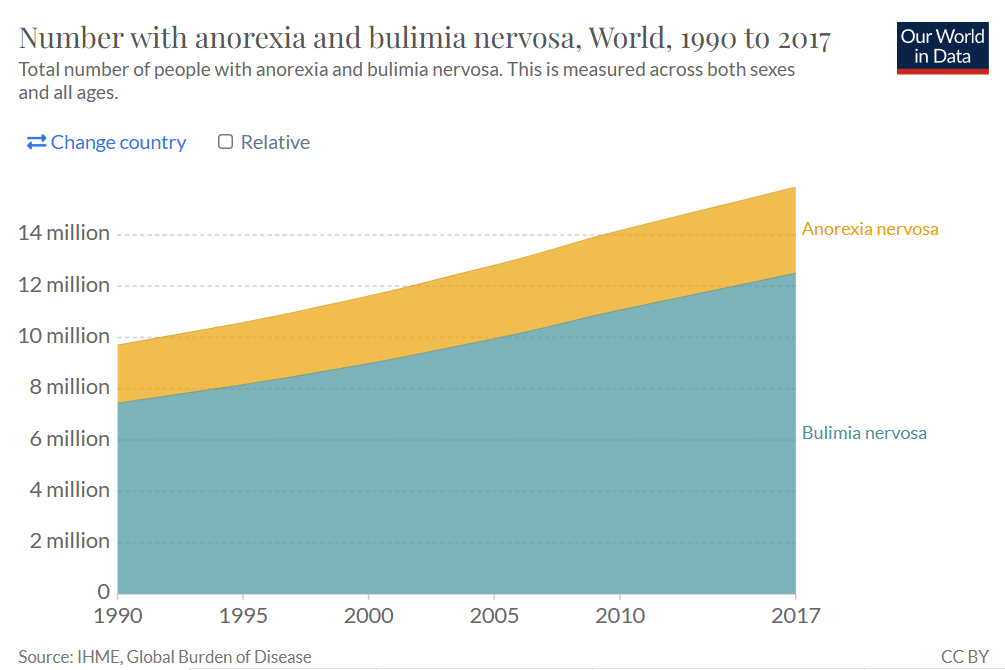

Eating disorders are among the most severe psychiatric conditions, often marked not only by psychological distress but also by high mortality and morbidity rates. Mortality refers to the risk of death, while morbidity captures the degree of health impairment or disease burden that interferes with daily functioning. In other words, eating disorders can be both deadly and deeply debilitating.

These disorders encompass a wide range of presentations:

Anorexia nervosa involves an intense fear of gaining weight and significant disturbances in body image, resulting in extreme food restriction and dangerously low body weight.

Bulimia nervosa is characterized by cycles of binge eating followed by compensatory behaviors such as vomiting or excessive exercise to avoid weight gain.

Binge eating disorder features repeated episodes of eating large quantities of food in short periods, typically accompanied by feelings of guilt and shame.

Pica involves the compulsive ingestion of non-food items, such as dirt or paper.

Rumination disorder is marked by repeated regurgitation of undigested food, which is then re-chewed, re-swallowed, or spit out.

Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) leads to a persistent failure to meet nutritional or energy needs, without the weight or shape concerns of anorexia.

Other specified feeding or eating disorders (OSFED) capture clinically significant disturbances that don't meet full criteria for the disorders above but still cause serious harm.

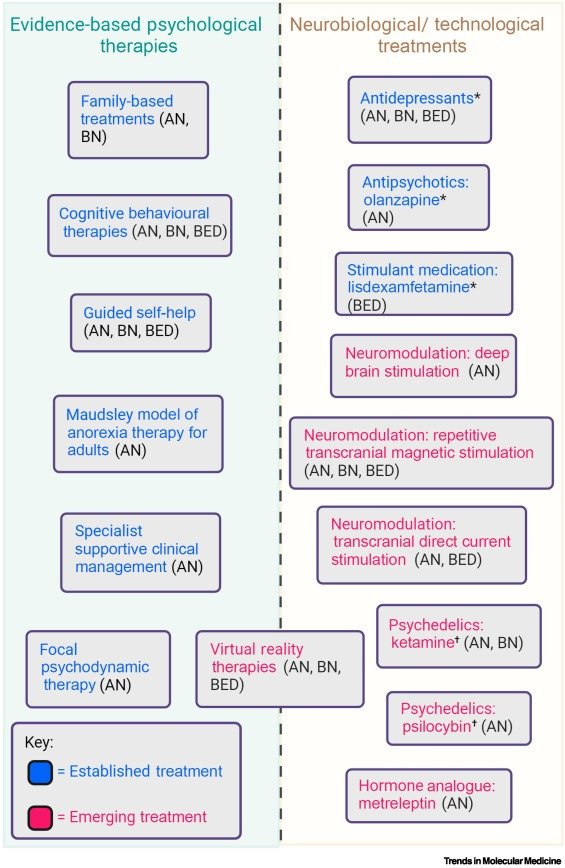

How do we treat these disorders?

Treatment typically combines psychological interventions and medical support. For adolescents, family-based treatment is often first-line. For adults, the following outpatient therapies are available: